18 What Product Should Drug Companies Sell? (can be skipped)

At the end of this chapter, the reader will understand:

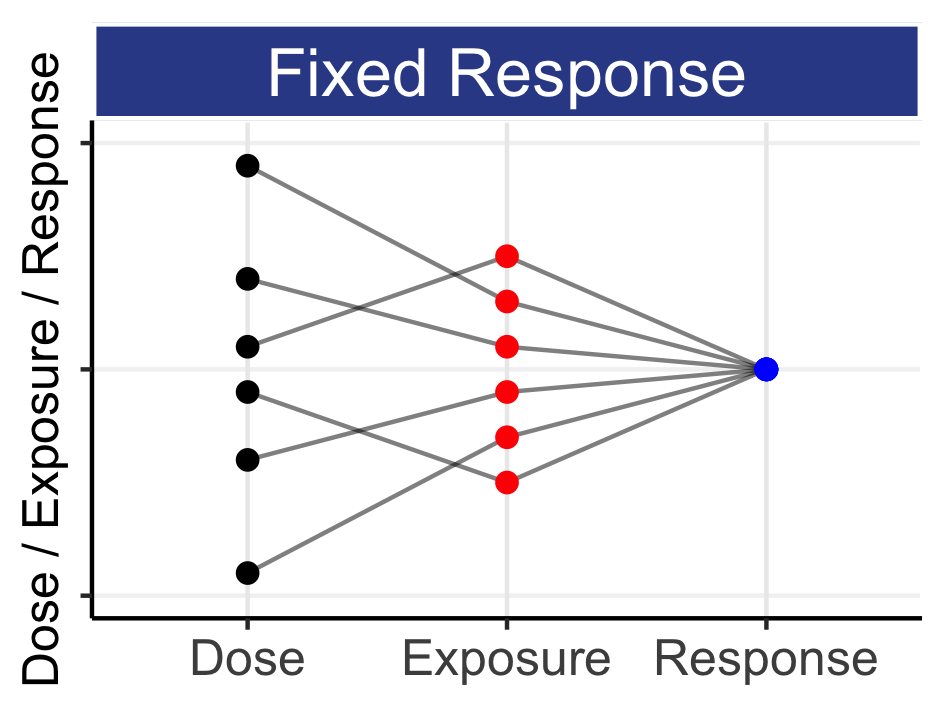

How historically drug manufacturers final product is simply a dosing regimen and a drug label; these are insufficient if we want to best use the drug for each patient, and very poor value relative to the cost of drug development.

How drug approval could use modern technologies to bring much more relevant information to the physician/patient that goes far beyond that offered by current drug labels.

At approval, a program/website with an interactive/smart, science-based, dose titration algorithm could accompany the drug label, helping physicians deliver personalised dosing.

Patient engagement, adherence and PROs data could, with permission, be collected across willing patients to enable multiple stakeholders (regulators, patient advocacy groups, payers) to further learn how different dosing regimens perform via Real World Evidence (RWE).

For the reader short on time, this chapter can be skipped; it may not be so useful. The aim of this chapter is to elaborate on what should/could be the final “product” of drug development. When I use my Apple computer, it has both hardware and software components. The computer user wants the best outcomes from their software, and without great software the wonders of the amazing hardware cannot be realised. If drug companies did computers, I would say they spend >99% of their R&D dollars on the hardware (making the drug and running the trials), and <1% on the software (providing the user with the right tools to unlock the full potential of the hardware). It is analogous giving someone the latest iPad with only Solitaire installed.

Historically the product the drug company sells is a dose of the drug (often using a price-per-dose (PPD) model). Despite the enormous R&D costs associated with developing a drug, the final product only comes with a drug label, a document that provides limited value to both the physician and patient.

The interaction/feedback between the user (the patient/physician team) and manufacturer (the drug company) is quite non-existent. How is the UX (user experience) being used to improve the product? Do drug companies ever hire UX people to improve their product and customer experience?

What if the product was more than simply a dose? The application of a science-based dose titration algorithm/program is one obvious extension, allowing the patient/physician to tailor the dose over time using, for example, a web-based tool (e.g. hosted by the FDA/EMA). However why not be more aspirational? Could we not aim for integrated/smart devices that could work with an app to record the time and dose of administrations and/or record PROs (e.g. the incidence and severity of key safety/tolerability measures)? These could prove immensely valuable both in terms of adherence and in allowing patients/physicians to accurately monitor the utility of the current dosing regimen. With patient consent, this data could even be shared (anonymously) with other patients/regulators/manufacturers and aggregated/analysed to provide real world evidence (RWE) of usage, and hence provide greater insight beyond the original clinical trials (e.g. imagine an app for patients with lung cancer that allows them to “chart” their tolerability profile and compare it to others, and see how these profiles changed for patients that titrated their dose).

We should look to learn from companies like Tesla and Apple to see how they collate user data to continually improve their products for current and new customers, and devices like the Freestyle Libre 2 System that continually records blood glucose levels in type 1 diabetes to provide forward looking predictions on glucose levels. People can be highly engaged to record/track their personal health data over time, whether that be via a running app, or an app designed for their particular illness, but we need to enable this. Finally, patient advocacy groups/charities/non-profits representing patients would truly appreciate these interactive apps/tools/dashboards, with potentially high engagement from patients to “make things better” and learn for both themselves and future patients.

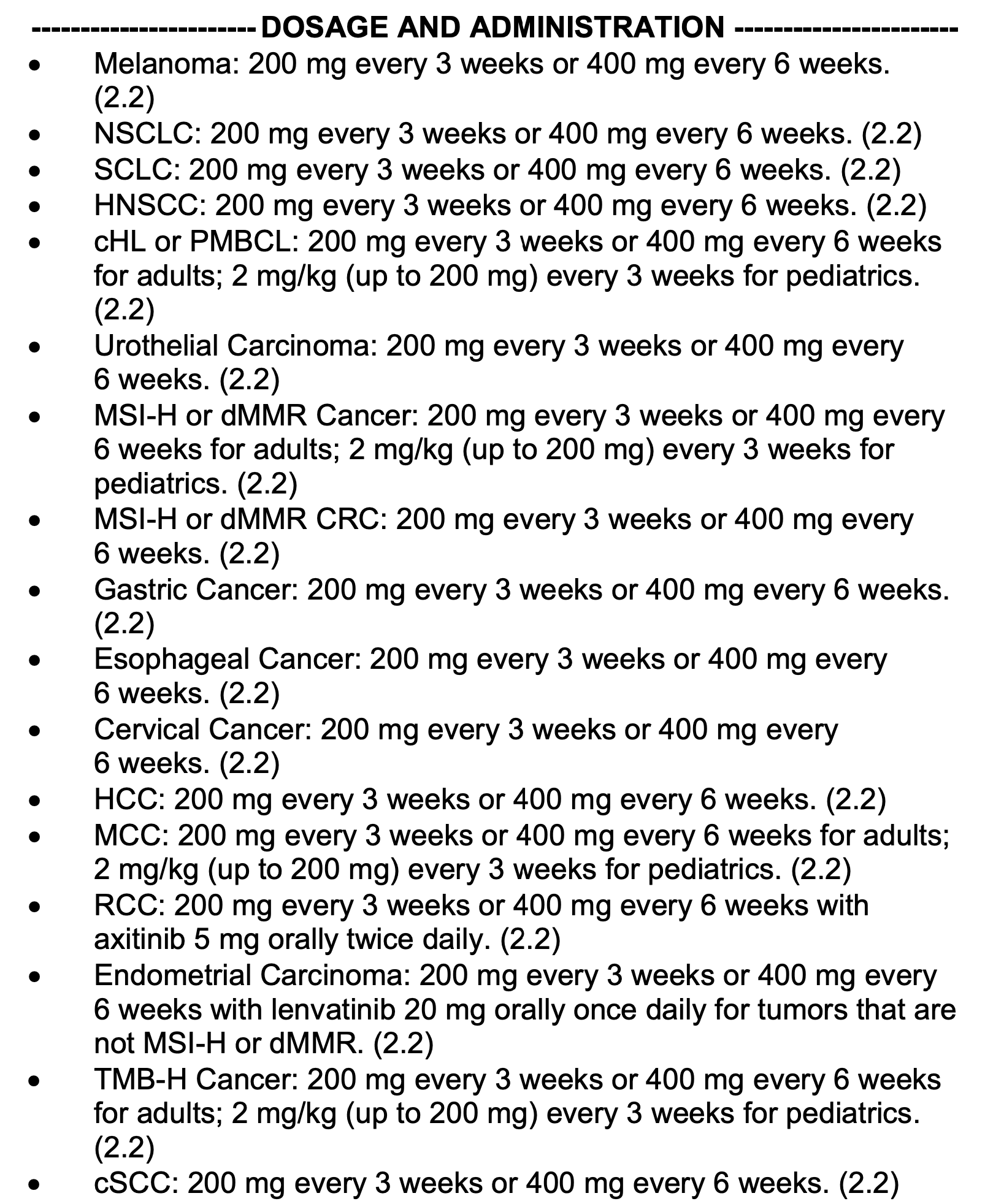

As an aside, I would like to make some observations on modern drug labels. The goal of the label is to highlight important information to the “end user”, the prescriber/patient. However the sequential presentation of copious pieces of information actually detracts from the overall usefulness to the prescriber/patient; they “cannot see the wood for the trees”! I see an analogy with my consulting work. On the one hand, I would like to include in my presentations sufficient details and results to ensure the full analysis and results are clear. However in doing so my “product”, the slide deck, can become far too large; the “end user” (the project team) do not have 3 hours to go through everything, but rather just need the key results (thus my additional material goes into the backup). Similarly, if we want the drug label to be most useful to prescribing physicians, are they really the best they could be? For example, the current FDA label for pembrolizumab (brand name Keytruda) extends to 106 pages; it provides copious information on a wide range of topics: the recommended dosing information for over 15 types of cancer, severe and fatal immune-mediated adverse reactions and laboratory abnormalities, when treatment should be withheld or discontinued, various drug combination and interaction information, clinical trial results etc. To illustrate how verbose and unwieldy the label is in parts, consider (a part of) the dosing information shown in Figure 18.1 below.

There is a lot of repetition in the above.

Imagine a physician is considering prescribing pembrolizumab in combination with carboplatin to a women of child bearing potential for the treatment of metastatic squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). They are specifically interested in the appropriateness/justification of the 400 mg every 6 weeks regimen (pages 54 and 99), concerned about fetal toxicity (page 52), and the dosing regimen used in the corresponding clinical trials (page 61). In a world where we are all rather impatient, this is painfully tiresome; trying to navigate the verbose drug label to find this information is both laborious and prone to error.

Now imagine that the same physician goes to the new FDA website for approved drugs, including pembrolizumab. Here they can directly select the drug and type of cancer, immediately obtaining only relevant information (think how 80% of the label has now been “moved to backup”). Now consider additional input fields that can capture key information relevant to their patient (sex, weight, previous treatments, renal function etc.) that can further be used to highlight relevant key results (e.g. fetal toxicity for women of child bearing potential). In addition, there could be “tabs” allowing the selection of real (anonymised) data from similar patients for key safety endpoints (e.g. rather than simply warn of the risk of neutropenia, show actual trial results of neutrophil counts over time for, say, women 25-35 years of age (like the patient)), with dynamic “dashboards” showing the risk of each grade of neutropenia as a function of different dosing regimens (numbers that are updated when combined with neutrophil counts from the patient after the initial treatment cycles etc.).

At the start of this book I discussed what would drug development look like if we could redesign it from scratch. I feel similarly about drug labels; I understand the history and understand the current format. However I am convinced we can do so much better. Primarily, we must put the needs of the end user (prescriber/patient) at the centre of everything we do. What do they need to know to ensure the drug dose regimens are used as effectively as possible? How can we help them, whilst also ensuring key safety information (e.g. contraindications, drug-drug interactions etc.) is also highlighted? How can we use technology to present the material as cleanly and crispy as possible? I think if all stakeholders and technology experts could sit down and prototype an interactive, web-based drug label, I am sure the final product would be light years ahead of, for example, the 106 page behemoth that is the current pembrolizumab label. We need more UX!

In summary, when we think about the final product of drug development, we should broaden our vision beyond simply a drug dose and drug label. The integration of modern technologies will substantially and continually improve the value and performance of the “product” to patients and provide informative and quantitative information to the prescriber. These tools combined will ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.