3 Why Patients Outcomes Must Come First

At the end of this chapter the reader will understand:

The need to put the outcomes of each and every patient at the centre of everything we do in drug development.

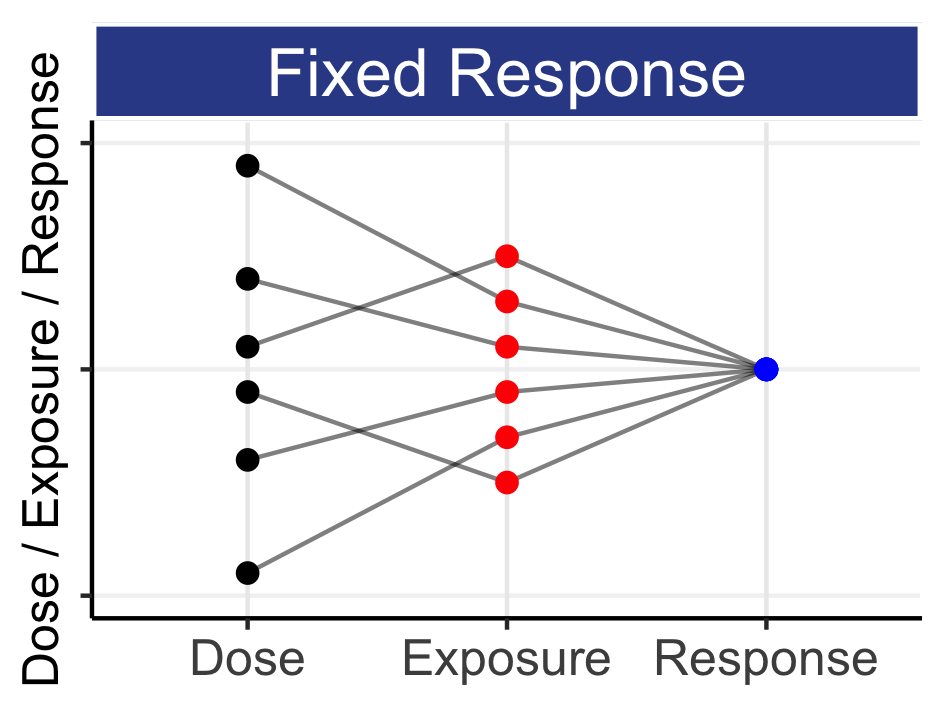

If we wish to improve individual patient outcomes, we must look beyond “average” responses from fixed-dose regimens.

That science-based dose titration algorithms can enable Personalised Dosing; we seek to understand the best starting dose, how and when to titrate, and when to consider halting treatment.

It may seem odd to need to say this, but drug development needs to put the outcomes of each and every patient at the centre of everything we do. To repeat:

Drug development needs to put the outcomes of each and every patient at the centre of everything we do.

It is perhaps easy for those involved in drug development to become detached from the realities of how the dose regimen each patient receives changes their life, both for good and bad. Rather, we might see summary tables by treatment arm (e.g. placebo and drug) with the proportions of responders and non-responders (with a “significant” P value), and the proportions of patients with (serious) adverse events. At a superficial level the pharmaceutical company may argue “job done”, and proceed to file for regulatory approval.

But if we pause for a moment, there are salient questions we should be asking. For example, consider the non-responders on drug; why did these patients not respond, or have an inadequate/poor response? Surely these patients should be investigated more thoroughly, since the dose regimen has failed them. Is seems wholly remiss to simply shrug our shoulders and conclude that the proposed dosing regimen “cures all but the incurable”. The central role of the dose regimen has been ignored. We can only conclude that this dose regimen failed these patients; this is very different from concluding there is no acceptable dosing regimen for these patients. Perhaps a patient dropped out due to unacceptable tolerability (consider a lower dose?) or had no tolerability issues, but just did not respond at this dose level (consider a higher dose?). Could we have not used any clinical endpoint or biomarker/imaging data to inform a science-based dose titration strategy, or simply asked the patient/physician team “Given your outcomes thus far, would you prefer to remain on the same dose, or consider a lower or higher dose?” Given our understanding of heterogeneity between patients in pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and their personal assessments of these effects, should we not plan to enable Personalised Dosing if we wish to put patient outcomes truly at the centre of drug development?

In oncology, a grade 2 toxicity of diarrhoea is defined as “Passing 4-6 more stools a day than your baseline” (generally only grade 3 and above are considered “severe” toxicities). How would we cope with such a debilitating experience? What impact would this have on our physiological and psychological states, or on our outlook towards future treatment cycles? Could we have worked that day, or fetched the kids from school? Behind a Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve in oncology, each downward step reflects a death of one or more patients. Just think about that. The dose didn’t work and someone died, and people close to that patient will be devastated. Did we really do everything we could to get the drug to work for that patient? If a patient with cancer showed little or no positive response after initial treatment cycles (e.g. no/minimal reduction in tumour size), should we have not titrated the dose higher? Perhaps the drug concentrations in this patient were much lower than other patients who received the same dose, and hence a higher dose may have truly helped this patient.

At an FDA-ASCO Virtual Workshop meeting entitled “Getting the Dose Right: Optimizing Dose Selection Strategies in Oncology” in May 2022, one panellist described intra-patient dose titrations, like that described above, as “problematic” from an analysis perspective. Indeed, such data cannot always be analysed using simple methods. Put bluntly, I see it as much more “problematic” that patients are dying or experiences severe toxicities because they are not receiving the right dose for them. We need to align trial designs and dosing regimens to put the outcomes of patients at the centre of everything we do, yet still generate meaningful data on how best to dose the drug. More complex analyses are a small price to pay for better patient outcomes; we can, and must, do this.

I had the recent opportunity to listen to a remarkable lady, Jill Feldman. You can find more information about her both before and after her diagnosis and treatment for lung cancer (link 1 below) and see a nice example of her patient advocacy work (link 2).

https://www.iaslc.org/journey-unlike-any-other-jill-feldman

She described the horrendous list of adverse events she experienced when receiving her first drug regimen, even after two dose reductions. Jill also described how she “tried to look my best” at physician visits to “make sure they didn’t give up on me”. She also described the dilemma she and her oncologist faced when she started a new drug regimen; go with the full dose, or “risk” a lower dose? The current drug label provided no guidance, since the right trials have not been done. Without this evidence, Jill went with the full dose, leading to what she described as “8 weeks of hell”. Jill is not the first, and will not be the last, patient to be in this position. We need to provide a much better evidence base to help patients like Jill make informed decisions.

In summary, when we put patients outcomes first, the drug development paradigm becomes clear. We need to determine 3 things:

Given a patient’s individual characteristics, what is the best initial drug and dosing regimen?

If/when the initial dosing regimen needs to be changed for efficacy and/or safety/tolerability, how best to do this; what is the best science-based dose titration algorithm? That is, based on clinical endpoints, biomarkers, imaging and/or patient reported outcomes (PROs), when should the dose be changed, and by how much.

Under what circumstances should the dosing regimen be halted? That is, there is no dose for the patient that has a sufficiently positive benefit-risk to justify continued dosing.

Although the above will not apply to every therapeutic area, the general principle should be clear; our goal is to obtain the best outcome for each and every patient via informed Personalised Dosing.