14 What Should Be The Role For Regulators?

At the end of this chapter, the reader will understand:

The roles and remit of a Net Benefit Regulator

The roles and remit of a Scientific Regulator

How a Net Benefit Regulator only considers average benefits/harms across groups of patients. They do not require any understanding of Population and/or Individual D-E-R relationships, or whether any fixed or dose titration algorithm is optimal in any way.

How a Net Benefit Regulator implicitly accepts no responsibility for the poor dosing choices (and hence poor patient outcomes) by the pharmaceutical company.

How a Scientific Regulator must determine whether the drug is going to be used in a way that is best for patients. To do this, they seek to understand and precisely quantify Population and/or Individual D-E-R relationships.

That a Scientific Regulator has a much greater task, responsibility and brings much greater value to both patients and society in general.

If we care about individual patient outcomes, we need Scientific Regulators!

Any discussion on drug development must consider the fundamental question, “What is the role of the regulator?” There are two main options with regards to regulators and the critical roles of dose and individual patient outcomes:

The Net Benefit Regulator: Does the proposed dosing regimen/algorithm yield Population benefits that outweigh the Population harms?

The Scientific Regulator: Does the proposed dosing regimen/algorithm maximise Population and/or Individual patient benefits and minimise Population and/or Individual patient harms?

To be clear, these are two totally different remits; the importance of which cannot be understated.

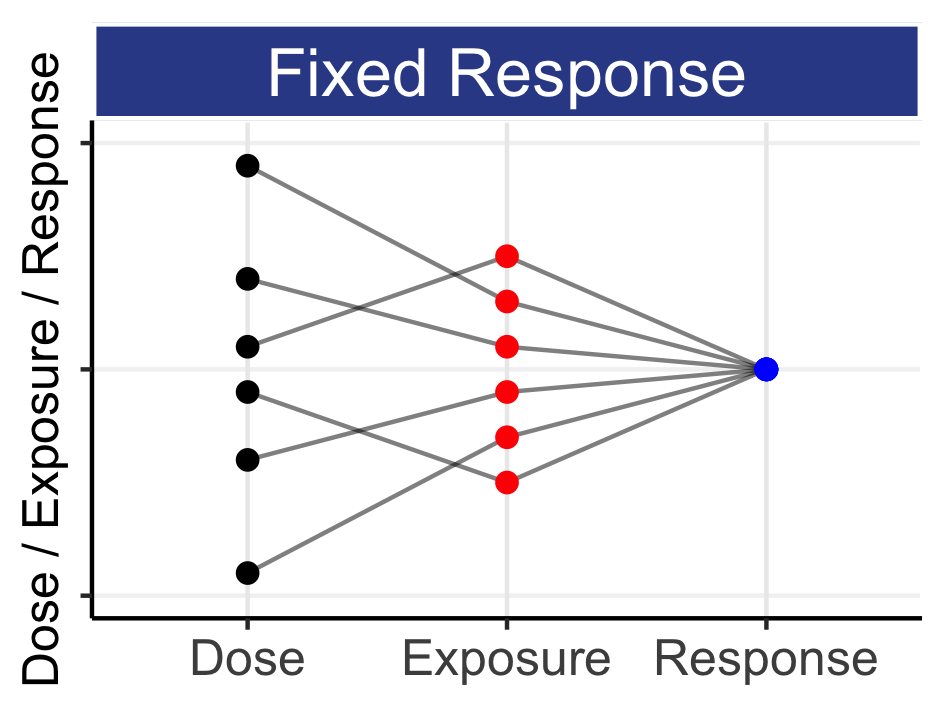

For the Net Benefit Regulator, the central role of dose is ignored, and individual patient outcomes are ignored. The average efficacy outcomes are simply contrasted with the average safety/tolerability outcomes, with no interest as to whether the dose is 10 mg or 100 mg. The shapes of the dose-response relationships are wholly ignored; the notion of “best use” of the drug is wholly ignored; the importance and influence of IIV is wholly ignored. In contrast, the Scientific Regulator has a much greater task, responsibility and brings much greater value to society. The Scientific Regulator must determine whether the drug is going to be used in a way that is best for patients or, stately conversely, will protect patients from receiving sub-optimal doses, and hence sub-optimal outcomes. Crucially, the evidence base needed for these two roles is completely different.

The Net Benefit Regulator may view the world as such. If a drug manufacturer seeks approval for a poorly chosen dose regimen, they may obtain approval based on a modestly positive overall net benefit profile (e.g. think about the many “high dose” oncology drugs that have been approved). In this scenario the subsequent uptake of their drug may be limited, with payers unwilling to reimburse a dosing regimen with mediocre or poor outcomes for many patients. However from the date of approval, patients who do receive the drug will be given the poorly chosen dose regimen, and some will suffer the consequences. Over time, physicians/academic groups may slowly learn, perhaps through trial and error, improved dosing strategies that differ from that described in the drug label; the drug label dosing information is then both obsolete and useless. I think such a scenario reflect terribly on both the drug developer and the regulator, because patients will bare the brunt of the inherently “laziness” from all parties. We need sound, science-based justifications for all approved dosing regimens.

As an example, consider a drug regimen that, relative to standard of care, prevents 10 cardiovascular deaths, but with 10 additional intracranial haemorrhages (bleeds within the skull). Based just on a simple assessment of utility (benefits versus harms), the drug could be approved by our Net Benefit Regulator (since preventing one death is “worth” having one intracranial haemorrhage). However what is a lower/titrated dose would prevent 9 cardiovascular deaths, but with only 1 additional intracranial haemorrhage? This regimen has a much higher utility, as the benefits more strongly outweigh the harms. In this example, do we want our regulator to simply decide to approve or not approve based on the dose regimen presented to them, or should we expect them to also consider the role of dose (i.e. the utility of different dosing regimens)? Do we not want our regulators to do such quantitative assessments, to ultimately approve the best drug regimens that yield the best patients outcomes?

The EMA states that the key principle underpinning a medicine’s assessment is (with my emphasis in bold):

“The balance between the benefits and risks of a medicine is the key principle guiding a medicine’s assessment. A medicine can only be authorised if its benefits outweigh the risks.

All medicines have benefits as well as risks. When assessing the evidence gathered on a medicine, EMA determines whether the benefits of the medicine outweigh its risks in the group of patients for whom the medicine is intended.

While the authorisation of a medicine is based on an overall positive balance between the benefits and risks at population level, each patient is different and before a medicine is used, doctors and their patient should judge whether this is the right treatment option for them based on the information available on the medicine and on the patient’s specific situation.”

Source: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/what-we-do/authorisation-medicines/how-ema-evaluates-medicines

As I understand the existing legislative remits for both the EMA and FDA, their current assessments are as Net-Benefit Regulators. As you might guess, I strongly feel this must change. Indeed I suspect most regulators would agree; it must be very disconcerting to be expected to approve any dosing regimen that causing significant and severe adverse events when the overall benefit-risk is modest, and there is no dose justification beyond “this is what we thought looked OK” based on wholly inadequate data (i.e. the sponsor just hasn’t bothered to design and run the trials needed to accurately and precisely quantify the D-E-R relationships). Historically there are examples where the FDA has challenged the appropriateness of the proposed dose (e.g. indacaterol), and their newly initiated Project Optimus specifically aims to ensure dose responses are accurately quantified in oncology. In oncology, it is very common for very high “one-size-fits-all” dose regimens to be presented for approval, even though no sound D-E-R efforts have been undertaken. Regulators are therefore forced to approve from a “net-benefit” perspective, even though the severity/frequency of a plethora of adverse events could be reduced at both the population and individual patient levels with more appropriate initial dosing and dose titration. The binary decision between approval and non-approval has been rightly questioned by regulators [1], who correctly identify the incoherence between how our knowledge of how best to use a new drug will evolve over time based on accruing information, and their current remit to simply approve or not approve a particular dosing regimen at a single point in time. A more “transitional” pathway would be more aligned with science.

As our understanding of science, pathophysiology and clinical pharmacology has evolved, so do our requirements of our regulators; we need them to be fit for purpose. We need regulators to be laser focussed on dose regimens. Given our modern understanding of heterogeneity between patients in both PK and PD, we need to change the laws that govern our regulators so they are Scientific Regulators. This additional remit may require further funding, but is essential if we want dosing regimen algorithms that are patient centric, and deliver the best outcomes for each and every patient.