2 My Motivation For This Book

Over the last 28 years I have worked in the pharmaceutical industry, either as an employee or as an external consultant. With a background in biostatistics and clinical pharmacology, my technical work/research has included:

Design and analysis of clinical trials (D-R trials, head-to-head trials, proof of concept/principle trials, first in man trials etc.)

Integrated dose-exposure-response (D-E-R) modelling and simulation across all trials and doses for sponsor decision making and regulatory submissions

Integrated analyses across multiple trials, drugs and doses (so called Model-Based Meta-Analyses (MBMA)) for accurate/precise comparative effectiveness evaluations and probability of success simulations

Optimal/adaptive trial designs for D-E-R modelling

Combination therapy trial design/analysis

Bayesian modelling

As a technical expert I use (all available) clinical trial data, mathematical models and simulations to provide integrated, quantitative analyses to guide drug development strategies. I have worked in most therapeutic areas, across phases 1-4 and all data types (continuous, categorical, count, survival etc.).

Fortunately for me, I have always found my work both interesting and challenging. In particular, I have strived to become an expert on D-R modelling, both by studying hundreds of D-R relationships across numerous types of clinical endpoints, and the use of appropriate mathematical models to describe such data.

However more importantly, I now view our clinical trial data from the perspective of each individual patient. For example, did their assigned dose provide them with no meaningful benefit, or caused them to experience real harms? Given my understanding of individual D-R relationships, I know we can do better for each patient, but we have to be open-minded when we think about what dose a patient should start with, and how we should best change the dose if needed.

I have also tried to understand the “big picture” of drug development, by considering the goals of others working in industry, regulatory authorities and reimbursement/payers. What is important to them, and what are their constraints? To select just a few observations:

Drug manufacturing teams being asked to initiate production/testing of dose levels before any clinical data has been collected/analysed.

Commercial teams wanting a “one-size-fits-all” dose, but being unaware of how this will negatively impact patient outcomes, adherence, and ultimately sales.

Project teams being asked to run ever smaller and faster development programs, but still expected to make informed, scientifically sound, decisions.

Internal regulatory teams wishing to follow the same path taken by other sponsors in earlier submissions (the safety strategy is the “same as last time” strategy).

External regulatory teams being asked to approve/reject new drug applications when the sponsor only provides two trials with “P<0.05” for a primary endpoint for a single dose level, and “tables and listings” for all safety data.

Payers being asked to reimburse expensive drugs for a patient, but having no idea whether the patient will actually respond.

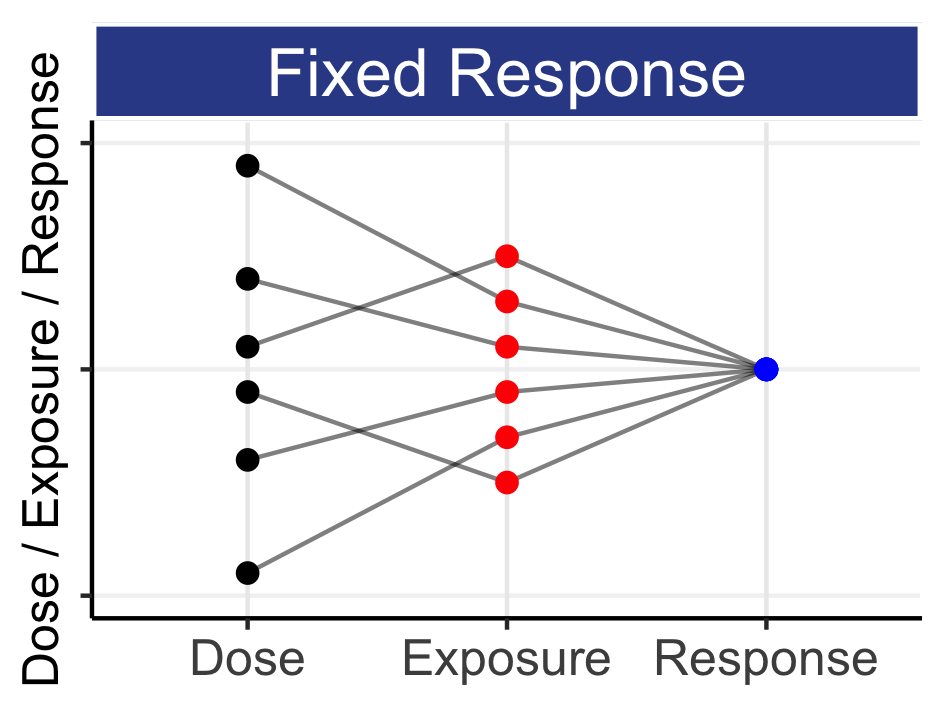

The above gives a first insight into why companies do what they currently do; a “sprint” to get 1-2 fixed-dose regimens into phase 3, demonstrate superiority over placebo and seek approval based on whatever safety data was observed. Dose response, individual patient outcomes and dose individualisation are on the periphery/absent in this process; fundamentally such a strategy is devoid of the concept of Personalised Dosing.

To be clear then, changing drug development will be very hard, with multiple stakeholders and historical/legacy frameworks that unfortunately conspire to make a difficult job even more difficult. However we must all endeavour to refocus drug development back to individual patient outcomes (are you with me?).

As a young analyst, I had the good fortune to talk with the brilliant Lewis Sheiner. He was a visionary in how he viewed drug development through both the sharp lens of clinical pharmacology and sound statistical analysis. When we think about drug development, we might ask, “What would Lewis Sheiner do?” He was a passionate advocate of scientific debate and progressive thinking, and remains my idol and someone I aspire to be more like.

My experiences in drug development have therefore led me to want to write this book, in the hope that it will help improve how we discuss drug development, how we design and analyse the required clinical trials, and how regulators use this comprehensive evidence base to ensure drugs are used optimally for all patients.

I think to be a good drug developer you must truly empathise with each patient taking your drug. If a patient is not responding, or experiences safety/tolerability issues, we must “own” this failure, learn from it, and strive to do better going forward both for this patient and the next.

Such a continual improvement mindset will result in better outcomes for patients. Better outcomes for patients will also benefit payers and the pharmaceutical industry; all stakeholders will benefit from the proposed “roadmap” for drug development herein.

Although you may not agree with everything in this book, I hope it will promote honest dialogue and real momentum for change. If they are willing to instigate real change, I am optimistic that leaders of regulatory agencies, industry, patient advocacy groups and payers can work closely together to make it happen.