9 Personalised Dosing; Patients Are Different

At the end of this chapter, the reader will understand:

Why patients are a highly heterogeneous group of individuals.

Understand adherence, and why it is important both for the patient and the pharmaceutical industry, but for difference reasons.

Why we need very wide dose ranges if we wish to truly maximise patient outcomes (and hence minimise “churn”).

Why patients should be able to make decisions around their dose with consideration to their treatment goals, outcomes and personal preferences.

That the consequences of getting the dose wrong goes well beyond the patient; their family, employer and society also suffer.

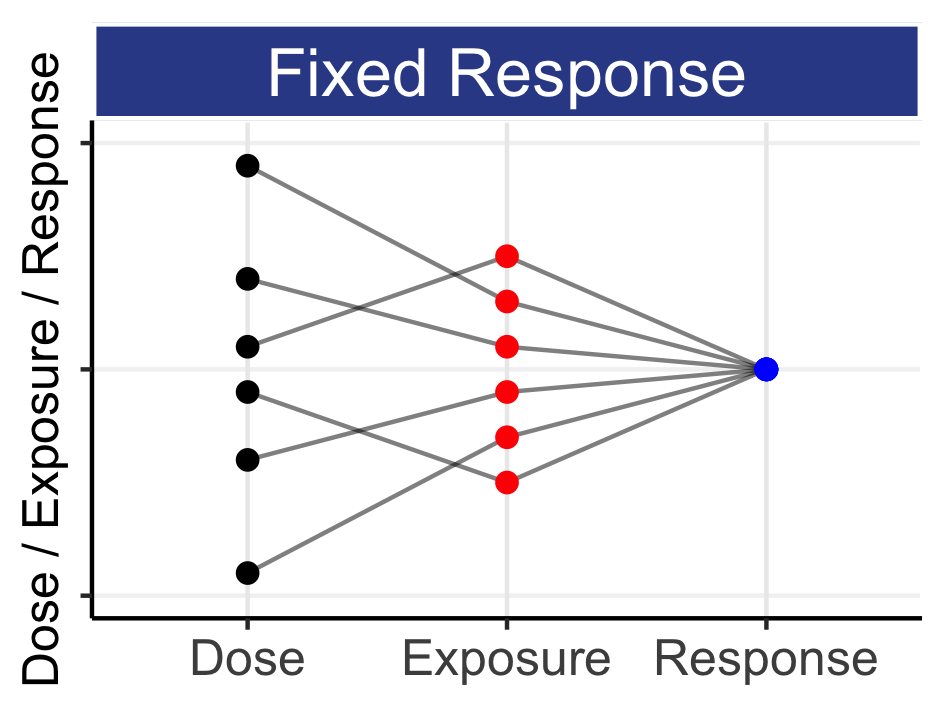

In previous sections we have introduced the idea that individual patient responses should be central to how we develop and use drugs, briefly covered the science of how doses lead to exposures that lead to responses, and that crucially patients have their own individual D-E-R relationships due to IIV in both PK and PD. Here we discuss this heterogeneity across patients in a much broader sense, and the consequences of this to adherence and the commercial success of the drug for the pharmaceutical company.

Patients are different. Not only do patients differ in simple measures such as age, weight and sex, each patient will have complex medical histories for the indication the drug will be used for. They may also have multiple comorbidities, and be taking a wide range of medications. In addition, they will have different lives, different values and different perspectives.

Personalised Dosing is about recognising this heterogeneity between patients and enabling each patient to find the right dose for them.

It is worthwhile considering many of the aspects around personalised dosing, and the consequences of getting the dose wrong.

Adherence may be defined as the extent to which patients take the drug regimen prescribed to them. If a patient considers their dosing regimen unacceptable in any way, they may decide to stop taking it. This may be due to many reasons, including the lack of efficacy, poor tolerability/safety, or finding the dosing regimen too burdensome. For both the patient and the pharmaceutical company, this failure is significant, but for very different reasons. For the patient, the drug regimen has failed to deliver, and they have wasted their time, money and perhaps experienced terrible adverse events. For the pharmaceutical company, they have lost a “customer” who will not return. They will not receive any future income from this patient, and the patient may tell other potential “customers” of their disappointing experience.

In a related conversation with a senior executive at a pharmaceutical company, we discussed the sales of one of their recently approved drugs. Two fixed doses were approved based on trials where patients typically received placebo, the lower dose (X mg) or the higher dose (2X mg). The indication, although not life threatening, would require the patient to continue taking the medication throughout their life (and there are very limited treatment options available in this indication). He mentioned that the company was disappointed that over 90% of patients prescribed to their drug had already stopped taking the drug at one year. From a tolerability perspective, I would describe the two approved dose levels qualitatively as “high” and “very high”. The two dose levels only spanned a 2-fold range with overlapping exposure ranges, and hence the tolerability profiles for each dose were not well separated; both were poor. Given that there was no urgency to aggressively dose each patient immediately, and that finding the right dose for each patient could deliver a “lifetime” of sales, it seems obvious (at least to me) that having a very wide of doses (perhaps starting at X/5 mg) could have allowed each patient to tailor their dose using an informed dose-titration algorithm. Since the trials were never done, we can only speculate that such an approach would have yielded greater adherence, better patient outcomes and higher sales, but the significant consequences/failures of “one-size-fits-all” dosing must be recognised by commercial teams and senior management within the pharmaceutical industry. If a pharmaceutical company chooses to only offer a single dose level (or two very similar dose levels) there is a substantial risk that many patient will “slip between their fingers” because they failed to offer sufficient flexibility with respect to dose.

The term “churn” is used in business as a measure of the number of customers who leave in a given time period. Thus in this example, the “churn” equates to losing 90% of patients within one year. This is wholly unacceptable to both patients and the pharmaceutical company, and “discovering” this post approval is truly awful. From a purely economic perspective, the pharmaceutical industry should seek to minimise “churn”. Fundamentally, any drug label with 1-2 dose levels will never enable personalised dosing. We need much wider dose ranges if we wish to truly maximise patient outcomes (and hence minimise “churn”).

It is also valuable to discuss how patients will differ in their attitudes to their outcomes on a given dosing regimen.

Consider Lilly and Oscar, two epileptic patients both experiencing, on average, 4 seizures a week prior to treatment. After an initial period of dose titration, both Lilly and Oscar are on the same dose and now only experiencing 1 seizure per week, but with intermittent episodes of nausea and vomiting that they both report as “mild”. Assuming they are in the middle of the approved dose range, should they continue on the same dose, reduce the dose, or increase the dose? This is a question we cannot answer, but the patient can. We should not pretend to know what is best for them, since this question directly relates to their experiences with the current dose, and their own attitudes to the perceived benefits and harms of the dose change. For Oscar, he may wish to lower the dose, as the “mild” nausea was actually quite debilitating for him, whereas Lilly might be keen to test the high dose, to see if further reductions in her seizure frequencies could be realised. This trade off between benefits and harms is often labelled the utility, and patients will differ in utility even when, on paper, they report identical outcomes. Thus Figure 6.1 can be augmented with an additional source of IIV, the variability between patients in their assessments on the utility of their responses. As drug developers, we should ensure a sound scientific framework for the approved dose range, but recognising patients interpretation of “best” for them will inherently be a personal decision (reached in dialogue with their physicians).

As a second example, consider personalised dosing for a drug approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA). As a primary endpoint in regulatory trials, approval in RA is often based on the proportion of patients who achieve ACR20 (ACR50), a composite scale where the patient needs to have improved by 20% (50%) in 5 of 7 domains, with these domains spanning objective and subjective measures of pain and inflammation. What do the improvements in the ACR20 (ACR50) actually mean for individual patients? What dose is best for a particular patient? One RA patient may consider their knee pain most important since it stops them taking daily walks with their dog, whilst another RA patient may consider their hip pain most important since it stops them driving to see friends. Whether a patient can find a dose that works for them may be based on many factors that we do currently captured in our clinical trials, but simply asking the patient “Would you like to continue on this dose, or try a higher or lower dose?” would enable the patient to consider their dose in consideration to their treatment goals, outcomes and personal preferences.

The importance of personalised dosing extends beyond the patient and the commercial value of continued adherence to the pharmaceutical company. When patients are poorly treated, the societal impact cannot be overstated. In RA and epilepsy, and indeed most therapeutic areas, if patients are poorly dosed, they will continue to experience significant difficulties in “life”, such as needing to take time off work, or needing to stop work all together. They may struggle to fulfill responsibilities at home and with their family, and their personal relationships may suffer. That is, the consequences of getting the dose wrong goes well beyond the patient; their family, employer and society also suffer. Similarly, when patients are over dosed, they may experience (severe) adverse events that could require hospitalisation, and lead to many of the same challenges with under dosing. Again, their family and society pay a price for this dosing failure. Equally, when we get the dose right for the patient, the benefits extend well beyond the patient. Thus getting the dose right for each patient is absolutely paramount.

I hope the importance and value of Personalised Dosing is fully appreciated by all stakeholders: governments, regulators, industry, patient advocacy groups and patients.